In early October this year, thousands of people left Ho Chi Minh City for their hometowns in the south eastern and western provinces, causing overnight congestion, as the local government eased the lockdown after more than two months of implementing Covid-19 preventation measures. How many people repatriated? Who were they and what were they doing in this city? What kind of situation had they been in that they just “went home first and dealt with the fallout later” despite the authorities' recommendation to stay?

In the first part, speaker Nguyen Duc Loc gave audience a sociological description of the "vulnerable group of people,” that is, most of those who left the city temporarily to evade the pandemic on the night of early October. This group was formed quickly after the 1986 Open-door policy from a large number of people moving from rural areas to the City in search of jobs and opportunities for change. According to the researchers' calculations, the group's annual remittances amounted to $6 billion, which is no less than the annual remittances that community of expatriates sent home to relatives. Still do they have to live in narrow urban spaces, work in relatively precarious conditions, be in a state of alienation/estrangement, and without cultural life. The speaker provided relatively comprehensive data on this group in Vietnamese urban areas, putting the Vietnamese situation in the context of economic paradigm shift with the rise of neo-liberalism in the world in the 70s and 80s. Though being just scientifically descriptive, the accurate data inevitably reminded listeners of Herbert Marcuse's "one-dimensional man" critique of the eponymous work published in 1964 in the United States, as well as Marxist ways of addressing the issues of poverty, the impoverishment of the working class, of the proletariat in 19th century in European cities under the influence of industrialization and modernization.

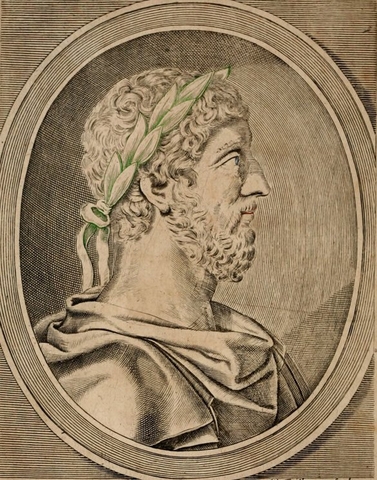

In the second part, the speaker Dinh Hong Phuc presented an overview of the ancient stoicism school. This school was prevailing more than 2,000 years ago and also witnessed a terrible pandemic at that time. Stoics considered philosophy as action, and focused their thoughts on "good way of life." They continued to develop the subjects of logic, ethics, and physics of the Greek tradition, and had various ideas when they combined them with philosophy to form a unified knowledge-practice genre. The practical teachings of Stoicism on emotional control, virtue development, and accurate judgement are practical lessons in manners in life, especially in 'emergency' and unusual social situations such as the pandemic. The most important lesson from them is: there are things outside that we can't affect, and there are things inside that we can affect. Just focus on the latter, such as our feelings, judgements, and actions. People often suffer much more in imagination than in reality. This lesson must be very helpful when people were faced with an epidemic, and in situations where there were so many uncontrollable factors.

A lot of questions were asked in the Q&A section. (1) How can we tell an action is right or wrong? One question may seem like about decision making skills, but in depth, it is a question of the theory of truth, which has been asked for thousands of years of philosophy history. (2) How can philosophy not only provide abstract, formal answers to specific, urgent practices? How can we actually take a further step rather than just general theoretical advice such as "know how to think critically” and "know yourself"? Overcoming the abyss of theory and practice has always been the unified ’knowledge-practice” dream of philosophy. Philosophy, in fact, has made great strides in trying to answer this question with the Marxist theory of 'praxis' and the modern pragmatic maxim. Perhaps most people these days would agree: ideas must be tried out in reality and praxis is the criterion of truth.