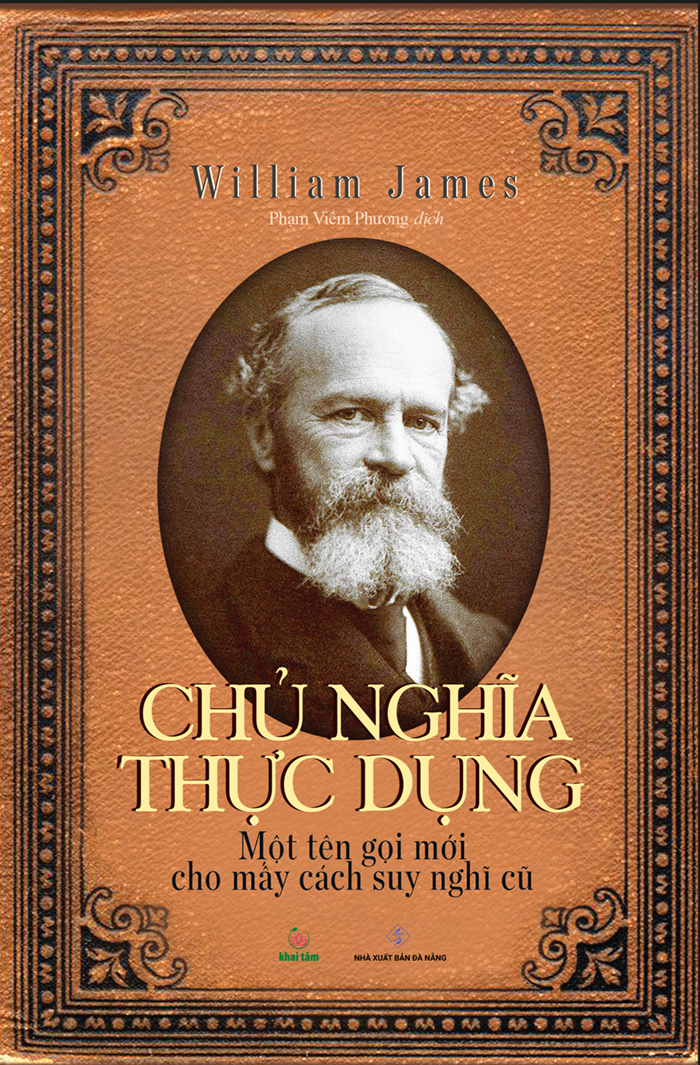

On an interview by Nigel Warburton on pragmatism in fivebooks.com, Robert Talisse recommended Pragmatism by William James as one of the five best books on pragmatism. This work has just been translated into Vietnamese by Phạm Viêm Phương and published by Sách Khai Tâm (https://www.khaitam.com/khai-tam-phat-hanh/chu-nghia-thuc-dung-bia-mem).

Here is the extract from the interview:

That links nicely to the next book in that it seems to be describing an approach to the world that is very sympathetic to scientific enquiry, with an emphasis on the correct way of going about discovering things about the world. It’s called Pragmatism and it’s by William James, best known as an early psychologist, and as brother of Henry James.

Interestingly, both James and Peirce were trained scientists. Peirce was a chemist and James studied anatomy and to be a physician. James is the one who popularizes the term ‘pragmatism’, and credits Peirce with having coined it. Jamesian pragmatism is, on the one hand, a theory of meaning — the pragmatic maxim that he picks up from Peirce — and, on the other hand, a theory of truth. He’s picking up from Peirce that pragmatism is a two-pronged idea, a conception of meaning and an epistemic conception. It’s intended to be a scientific conception of meaning, it’s supposed to be pulled out of a laboratory, to give one a sense of the understanding of meaning that scientists employ when they do their experiments. James thinks that meaning is to be cashed out in terms of the implications of believing a proposition or a statement for your behaviour or conduct. James thinks that part of the meaning of a statement might even be — and this is one of James’s own innovations, something that Peirce gets very cross about — its implications for your psychological wellbeing.

This is where pragmatism goes a bit odd, because doesn’t William James use that style of thinking to suggest that when somebody says they believe in God that is really a statement about the psychological effects of that belief?

Yes, this is the way the view starts moving in James’s hands. What’s really important to understanding what motivates James to say that kind of thing is that he is biographically deeply torn. There is his scientific training: he is still regarded as the father of modern experimental psychology, he knows how to run a lab and do experiments. When one reads his The Principles of Psychology it’s very sophisticated measurement of difficult things to measure. He’s really good at the science. But temperamentally he is drawn to various kinds of spiritualism. He’s a religious guy. He believes, in parts of his life, in ghosts and spirits. In fact, towards the end of his life, he started trying to investigate, in scientific ways, parapsychological and paranormal things. So he’s got an almost spooky side to him, and he sees pragmatism as a kind of empiricism which — unlike the logical empiricism of the logical positivists — is going to be more hospitable to religion, spirituality, and values, in a very broad sense of that term. James is constantly talking about “feeling at home in the universe.” Part of what motivates his pragmatism is the attempt to reconcile a scientific, hard-nosed view of the world with a spiritualistic, religious conception of our place in it, these two drives that he personally felt quite strongly.

So the way it works is that we’re supposed to understand the meanings of propositions in terms of their implications for our behaviour — our behaviour very broadly defined to include our psychological moods and comportments and attitudes. We understand what the proposition means by how it would lead us to act. Then, there’s the conception of the truth, and a proposition is true in so far as it leads us to act in a way that is successful, or a way that is good for us to act. It’s a very puzzling conception of truth, philosophically speaking. It’s also very difficult to formulate it in a way that makes it sound anything but silly. When James says things that are not as cautious as they should be like, “Truth is what works,” he invites — unnecessarily I should say — a lot of well-placed criticism. Truth is what works? If I believe that I’m a very handsome guy, that could work for all kinds of purposes. It might not be true. These are the kinds of statements that earlier in the 1900s people like Bertrand Russell and G.E. Moore had a field day with. It seemed like a crazy conception of truth. But I think it’s a more nuanced view than James sometimes suggests. It’s a view that says, we have beliefs for purposes. Beliefs are tools. A belief is like a hammer or a pair of scissors. It’s supposed to do things, behaviourally, it’s supposed to guide our actions. James thinks that the truth of a belief is to be understood in terms of the success it brings to our action when it serves as our guide. When you put it that way, there are still all kinds of objections and problems that can be raised, but it’s not so obviously the easily dismissible, silly idea that one gets when one leaves it at “the truth is what works” formulation.

And one of the ways that William James’s writing works, pragmatically, is that he’s a superb writer at the sentence level, like his brother.

Absolutely. If anybody ever wants to read a book of philosophy that’s about truth and meaning and religion and metaphysics that is a breeze — that you could almost read at the poolside — James’s Pragmatism is a brilliantly written piece of philosophy. I don’t think it’s too far of a stretch to say that William was a better writer than his brother.

Source: https://fivebooks.com/best-books/robert-talisse-on-pragmatism/