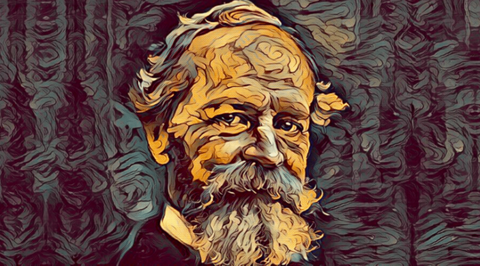

The philosophical work A treatise concerning the principles of human knowledge (1710) is a masterpiece by George Berkely, published at his age of 25. This treatise holds an important position in the history of empiricism in particular and of Western philosophy in general. Its central contention is the proposition that the physical world cannot exist independently of the perceiving mind, through the expression "esse est percipi" (to be is to be perceived). George Berkeley's purpose in writing this work, as he said, is "to try if I can discover what those Principles are which have introduced all that doubtfulness and uncertainty, those absurdities and contradictions, into the several sects of philosophy; insomuch that the wisest men have thought our ignorance incurable, conceiving it to arise from the natural dullness and limitation of our faculties."

Translated into Vietnamese by Đinh Hồng Phúc and Mai Sơn with the revision of philosopher Bùi Văn Nam Sơn, this work was published by Tri Thức publisher in 2013.

|

|

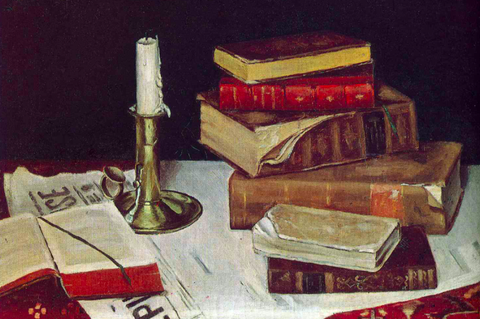

| Title page of the first edition (1710) | Front page of Vietnamese translation (2013) |

The structure of the book consists of: Introduction (including 25 subsections) and Part I (including 156 subsections).

In the Introduction, Berkeley mainly criticized Locke's theory of abstract Ideas as a fundamental flawed Principle that "introduced all that Doubtfulness and Uncertainty, those Absurdities and Contradictions into the several Sects of Philosophy" (§4). For Locke and many other philosophers, the Mind "hath a power of framing abstract Ideas" (§6) by reducing qualities or properties of individual objects to simple components to derive ones that individual objects have in common, that is, the general. Berkeley attacked this theory with a contention that abstracting such ideas is something we can't do, and the origin of that flaw is the mistaken view of language: the purpose of language is to convey our ideas, and every meaningful name represents an abstract idea. For Berkeley, language represents only general ideas, not any abstract idea. Therefore, the way we can get to the truth and avoid all mistakes is to "clear the first Principles of Knowledge, from the embarras and delusion of Words" (§25).

Berkeley developed the entire content of Part I into 156 subsections in a row. Later, to help readers better understand Berkeley's presentations, the editors of Berkeley's works divided Part I into sub-categories: 1) Objects and Subjects of knowledge (§§1-2); 2) Arguments for Immaterialism (§§3-33); 3) Objections and Replies (§§34-84); and Consequences of Berkeley’ view (§§85-156).

First, in the first subgroup, Berkeley identified the subjects and objects of human knowledge. The objects of knowledge are ideas, and these ideas are divided into three categories: "actually imprinted on the Senses," "perceived by attending to the Passions and Operations of the Mind," and "formed by help of Memory and Imagination." The subjects of Knowledge, according to Berkeley, are not particular persons, but "spirit," "mind," "soul," or "self." This is a dynamic perceiving entity, which is completely different from ideas, which perceives ideas, which is where ideas exist: "for the Existence of an Idea consists in being perceived."

After identifying the objects and subjects of knowledge, Berkeley began to develop arguments supporting immaterialism through the next 30 subsections.

Berkeley's initial argument for immaterialism is that "there is not any other Substance than Spirit" (§7). This argument was raised to refute the doctrine of abstract ideas, which argues that all perceivable objects are independent beings and completely different from those which are perceived. For Berkeley, this distinction proved unjustified because abstraction went beyond its sphere of influence. I can only abstract an object to the extent that I recognize it dependently, but I can't separate it from the spiritual perception in me of it as a self-contained entity: "all those Bodies which compose the mighty Frame of the World, have not any Subsistence without a Mind." As such, the world with only one substance is the mind, and the so-called "matter" or "substratum" of ideas cannot be regarded as substance.

According to Berkeley, because things that we directly perceive all have secondary qualities and because they exist only in the mind, what we perceive is "spiritual ideas," not objects in the external world. Furthermore, on the basis of the principle of similarity, only ideas are similar to ideas, not to anything unperceivable, and he deduced that there is no similarity to ideas in the so-called material. "Any color or extensive quantity, or any perceivable property, can absolutely not exist in an unthinking subject, outside of mind," he affirmed. In this regard, Berkeley was pointing out the problem of materialism, specifically the following: One, the idea of materiality (or tangible substance) itself is a contradictory idea, in that it holds that properties that are only found in the spiritual substance can be also found in the non-spiritual body. Second, materialism is leading us to indirect realism of perception, leading to skepticism. Though ideas cannot exist on their own, they are assumed by materialists to be copies of spiritually independent beings (§15). But objects of the senses are constantly changing, while their originals are thought to be invariant, so they can't be honest copies of their originals. Third, there is no distinct meaning annexed to the concept of material substance (§17), because the concepts of substance and substratum, of what is the lift for extensive quantity, are too ambiguous and abstract that are inconceivable.

Following the master argument that no object can exist outside the mind, since such objects are, in principle, impossible to perceive, Berkeley reviewed and responded to arguments that refuted the philosophy of immaterialism (subsection §34 to subsection §84). Respondence to these counterarguments is also his statements about his idealism, which is later called subjective idealism. In general, these counterarguments can be grouped into major groups: 1) of ordinary people; 2) of scientists; and 3) of religion.

First of all, with arguments from ordinary people, Berkeley answered that neither did his philosophical system deny the existence of anything perceptible, nor firsthand information, - whether they existed or not did not matter, as long as they existed "in the spirit" for him; what he refuted was that materialists insist on the existence of an imperceptible substance called a "material" or "tangible substance" that supported beings with shapes, extensive quantity, motion, etc.

In response to the counterarguments from the scientific side, Berkeley replied that his philosophical system was not harmful to science, if it was properly understood. It's not science's job to present metaphysical explanations, but to present the laws of operation observed in the natural world as clearly as possible. So his idealism and immaterialism are not only compatible with the right scientific practice, but they are also really useful for science to rule out the ambiguous concepts that interfere with human consciousness.

Finally, there are counterarguments from the religious side. Berkeley says that although the language of the Bible refers to "materials" (e.g., mountains, rivers, vegetation, people, etc.), it does not have the same way of understanding as the materialists' one, that is, material is an imperceptible subtratrum. And since the true role of language is "marking our Conceptions, or Things only as they are known and perceived by us" (§83), his principles of presentation do not contradict the rules of language. Furthermore, the case of miracles in the Bible (Moise's scepter turned into a snake, water turned into alcohol) does not make them lose their exerted power, because it acknowledges that "the scepter turned into a snake" and "water turned into alcohol" are real. Therefore, similar to the two groups of arguments mentioned above, his immaterialism is not as dangerous as mistaken.

After responding to possible counterarguments from various sides, Berkeley spent the next 49 subsections, from §85 to §134, considering the benefits his theory could bring to human cognitive activities, namely, philosophy, science, and religion.

In general, the benefit that immaterialism can bring to philosophy is that it eliminates all of the "several difficult and obscure Questions, on which abundance of Speculation hath been thrown away" (§85), and once it is done, skepticism and atheism will no longer have any basis for survival, people will save much effort and time in the search of truth.

In terms of science, the benefits of this theory are considered by Berkeley in the "two great provinces'' of natural science and mathematics. In the field of natural science, his aim is to counter the skeptics' contention that the true nature of things is something we cannot know in principle. The basis of this contention is the scientific interpretation of Newtonian mechanics. Berkeley's view is that in principle, we always understand the true nature of things. Scientists should not try to find the cause of impact in the natural world, because the principles of mechanics cannot help us explain the fundamental laws of nature such as attraction and cohesion of things. The principle of "analogies between events" in scientists is very susceptible to the trend of absolutization, "extending its Knowledge into general Theoremes", thus "to the prejudice of Truth" (§106). The philosophical principle of immaterialism will help scientists realize that the greatest analogy of all events is to regard the natural world as the work of a wise and benevolent agency, God, and the only correct way to interpret them is by final causes, not by corporeal causes.

The last subsections of the Principles from §135 to §156, Berkeley considered spirits and God. Since Spirit is "the only supporting substance in which unthinking beings or ideas can exist" (§135), and, according to the principle of analogy, only ideas are similar to ideas, we cannot create a spiritual idea. We can only create a concept of spirit. Concepts are different from ideas in that they do not present a picture of the true content of the object being marked, but rather is the result of reflection between our ideas and those in the minds of others according to the principle of analogy.

Let's just say that we don't have any idea of others' spirits, we can still infer the existence of those spirits by observing the changes in our perceptual spirits. We can derive the concept of spirit from the observation of our own self or soul, and from that, "we know other Spirits by means of our own Soul" (§140). The reason for us to do this is because of God's agency, which is present everywhere and provides a stable background on which all causal relationships take place so that we can capture the spirit of others. "He alone it is who upholding all Things by the Word of his Power, maintains that Intercourse between Spirits, whereby they are able to perceive the Existence of each other"

As we can see, Berkeley's entire philosophical project was done in this work, A treatise concerning the principles of human knowledge, justifies the truths in the Gospel of God's existence as the true substance of all beings, all natural order, and the fountain of all human authentic perception. Therefore, his philosophy, namely immaterialism, has no other task than to dispel all misconceptions about God and evoke a "pious Sense of the Presence of God" for them to "reverence and embrace the salutary Truths of the Gospel" (§156).